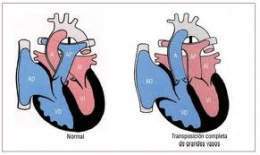

Anomaly of the great vessels. In medicine, transposition of the great vessels (TGV) refers to a group of congenital heart defects in which there is an abnormal arrangement of the main blood vessels that leave the heart: the superior and / or inferior vena cava , the pulmonary artery, the pulmonary veins and the aorta. If only the arteries (pulmonary artery and aorta) are affected, the disorder is known as transposition of the great arteries.

In the child , important and diagnosable syndromes are observed , caused by the abnormal development of the aortic arch and the aberrant position of one or more vessels originating in it. Early diagnosis is of utmost importance , because early surgical intervention saves life and prevents many cases of serious disease .

Many insignificant aberrations in the origin and course of the intrathoracic arteries go unnoticed because, despite their abnormal location, they do not compress the trachea or esophagus .

Etiology

The development of the aortic arch is effected by a series of evolutions of the paired primitive aortic arches.

Frequency

There are many such abnormalities, but only a few of them cause symptoms. The most common disorder of this symptomatic group is the double aortic arch. Wolman, in his remarkable 1939 communication , was able to find already 6 cases in the medical literature.

It is very well to conjecture that in North America alone , more than 100 cases have been operated since that date. The right aortic arch is not uncommon either, but there is still a higher proportion of cases that do not produce symptoms. They only cause manifestations when the surrounding annulus is completed by a patent ductus arteriosus , a ligamentum arteriosum, or another aberrant vessel.

Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms caused depend on the location of the aberrant vessel or vessels and the compression produced in the esophagus and trachea. In the double aortic arch, a combination of respiratory and digestive signs can be expected, with a predominance of respiratory signs. There is dyspnea from birth, or it occurs only after several weeks. Stridulous respiration is observed in most cases, although expiratory rather than inspiratory stridor is heard more often. Stridor often persists during sleep and is intensified by crying. There may be permanent or episodic cyanosis .

Feeding tends to initiate or intensify stridor, and to cause or increase dyspnea and cyanosis. The bottle is frequently swallowed poorly , and regurgitation may occur. The vomit sometimes contains fresh or altered blood . The food can also stimulate paroxysmal cough. All signs are aggravated by respiratory infections that repeatedly strike these children. During infections, severe dyspnea and false croup may occur, signs that indicate acute laryngotracheobronchitis. In severe cases, children prefer to lie down and with the head in maximum extension, since the flexion of the neckintensifies dyspnea. The metallic voice is typical.

The right aortic arch itself produces few or no symptoms. Rarely, as it moves to the right rather than to the left, it compresses the trachea or the right lung bronchi . In this case, compression produces atelectasis or pulmonary emphysema , or both. The disorder is most common when it is a branch of a complete vascular ring and the others are a patent ductus arteriosus, a ligament, or a right subclavian artery. The vascular ring is clinically indistinguishable from a double aortic arch.

The most common single-vessel abnormality is found in the left subclavian artery with an aberrant origin on the right side of the arch and from the arch to the left side. It usually crosses behind the esophagus, less frequently between the esophagus and the trachea, or, rarely, in front of the trachea. If symptoms occur, they can be limited to dysphagia , but if you follow one of the two less frequent routes, respiratory symptoms can also occur.

The presence of respiratory symptoms without esophageal symptoms suggests that the trachea is compressed by an abnormal innominate artery. There may be no symptoms or signs at birth, yet they appear and intensify in the first months of life, only to disappear later. In these circumstances, episodes of apnea , laxity, and cyanosis are possible , as in other forms of tracheal compression, caused by aberrant vessels.

Roentgenological diagnosis

Normalized atelectasis or emphysema of the newborn , if persistent, should suggest vascular compression of a main bronchus. Exposure of the trachea in the standard anteroposterior and lateral views reveals a stenosis above the carina, in addition to one of a horizontal or sagittal deviation. The most effective procedure for diagnosis is the esophagram, after swallowing the barium , which shows abnormalities of the esophageal contour. The use of high voltages in the printing of the films, intensifies the contrast between the air and the soft tissues and helps to identify a tracheal compression.

When the esophagus is filled with barium, its forward deviation is observed by a pulsating, spherical body. The instantaneous and localized roentgenograms reveal constriction from both sides, and in the lateral projection, they show deep depression in front and behind. The aberrant right subclavian artery with a usual left-to-right course produces an oblique defect on the posterior aspect of the esophagus, approximately 0.5 cm wide and 3 to 4 cm long.

Contrast tracheograms and angiograms are not indicated, except in rare cases where standard roentgenograms and esophagograms are not sufficient to establish the suspected diagnosis. They are useful to the surgeon by indicating whether the anterior or posterior arch is better, thus deciding which one to tie. The incision used may depend on this information.

Forecast

The prognosis varies according to the degree of tracheal obstruction, the nature of the anomaly, and the treatment instituted. Children with early symptoms will be carefully observed, because often, along with development, strangulation of the annulus increases. Sudden death may occur. Lower respiratory tract infections, sometimes pneumonia , but in most cases, conditions resembling severe laryngotracheobronchitis are seen frequently . After surgical correction, even if the dyspnea disappears quickly, the stridor is likely to persist for many months.

Treatment

Surgical correction has been effectively achieved in all types of ring-shaped vascular abnormalities. The surgical risk is still great. In choosing the right time for the operation, the surgical hazard should be weighed against the degree of respiratory distress. If this is severe from the beginning, the operation is indicated in the neonatal period. If the operation can be deferred, any respiratory infection should be treated early and vigorously with antimicrobial agents.

The most frequent problem that occurs in the postoperative period is the persistence of the respiratory disorder once the obstruction vessel has been excised. Often, when the trachea is not able to recover its normal dimensions, this is due to the existence of hypoplastic segments of the same, which frequently require a subsequent intervention. In some cases, braces made from an autologous rib have been used in cases of symptomatic tracheomalacia. In certain circumstances, a tracheostomy is essential .